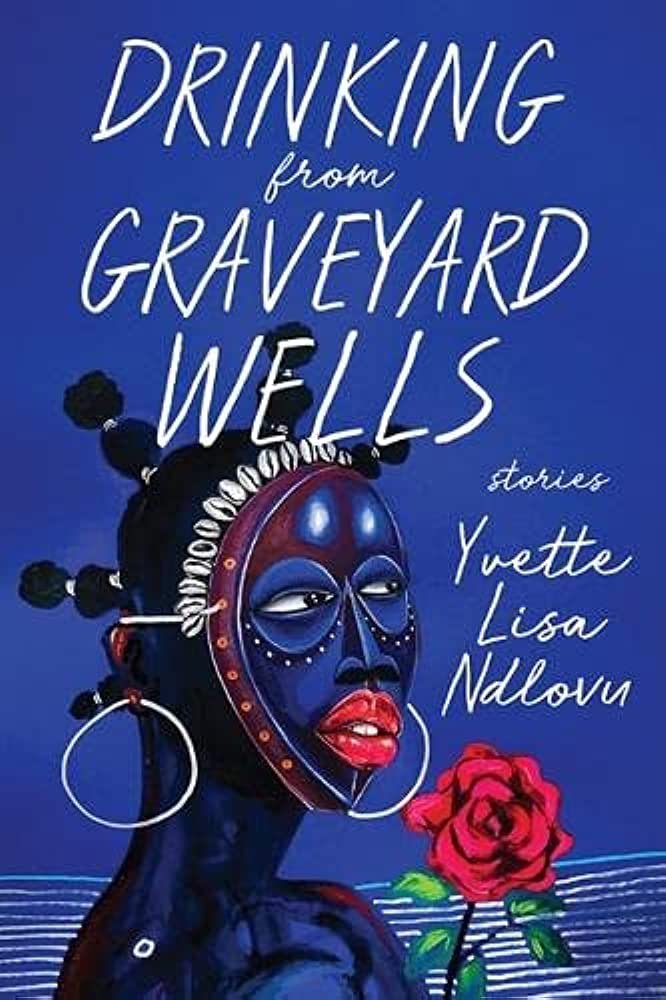

Even the gods are bastards: A review of Yvette Lisa Ndlovu’s DRINKING FROM GRAVEYARD WELLS

Yvette Lisa Ndlovu’s debut short story collection, Drinking from Graveyard Wells, glimpses into the lives of African women, be they goddesses or ghosts, broke college student or town gossip. This is a collection of blood-boiling big ideas, asking: what if life and death are simply unfair? What if the white boy gets to become a millionaire by building a rideshare app based on Zimbabwean customs? What if the patriarchy persists, even in the afterlife? Ndlovu, a real-life sarungano, writes to make us rage right alongside the women in these stories while still insisting that the lessons we learn from storytelling are remedies, but not in the way we might expect.

A real triumph and delight of Drinking from Graveyard Wells lies in its fearless condemnation of the powers that be—even the gods themselves. “When Death Comes to Find You” envisions a capitalist hellscape: a world where debt in life transcends to debt in death and diamond miners must participate in an immortal toil. The story asserts that “even the afterlife is made for the rich.” In “The Soul Would Have No Rainbow,” a granddaughter receives a letter from her late grandmother revealing that “in the heavens all the gods were arrogant bastards.” Ndlovu forces us to reckon with the possibility of cosmic inequity, that omnipotent power still corrupts.

Despite the seemingly hopeless conception of an unjust afterlife, Ndlovu does seem to offer up the antidote. “The Carnivore’s Lollipop” introduces us to ngano, fables and fairytales from the Shona tradition that, in this collection, often work as warnings of divine justice. Ngano about reparations are interspersed throughout this story as the narrator is duped into a multi-level marketing scheme, buying and breeding boxes of ants to sell back to a drug company. When the company gets dissolved by the CEO, we realize what reparations look like when people who are in possession of ants (raised on a carnivore diet) decide to show up to the protest. So often, marginalized people are asked to turn the other cheek in the face of injustice. But, in these stories, Ndlovu offers an alternate solution: revenge. In “Red Cloth, White Giraffe,” a woman must remain on earth until her former husband pays off the rest of her bride price to the men in her family. The threat on the other side of this is that the woman might become a ngozi, an avenging spirit, capable of levying a visceral justice.

In “Plumtree: True Stories,” we receive a series of vignettes, many of which introduce new iterations of ngano and Black spirituality. The title reads as a radical act, casting Black spirit as true, as fact, and as essential, placing Ndlovu firmly in the midst of Black writers like Akwaeke Emezi and others whose work gives credence to the divine.

Drinking from Graveyard Wells explores what it means to grapple with those in power by allowing us to imagine the gods as absolute bastards. The collection insists too that storytelling and oral histories serve as reminders that justice isn’t freely given, it’s taken. Kicking and screaming, Ndlovu’s debut collection demands to be seen.

Erica Frederick is a queer, Haitian American writer and MFA candidate in fiction at Syracuse University. She currently serves as the fiction coordinator for The Best of the Net Anthology. Her work has appeared in Split Lip Magazine, Storm Cellar, and Forward: 21st Century Flash Fiction. She has received fellowships from VIDA, Lambda Literary, and the Hurston/Wright Foundation. You can find her tweeting into the void @ericafrederick.